A Conversation with Dr. Stephanie Hartselle

We spoke with Dr. Stephanie Hartselle ahead of her talk at the Newport Art Museum, exploring the evolving role of psychedelics in mental healthcare and their intersection with creativity and artistic expression.

Dr. Hartselle is board certified in both pediatric and adult psychiatry, with an MD from Northwestern University and training at NYU/Bellevue and Brown University, where she served as chief resident. Currently a Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Brown University, she specializes in sleep disorders, OCD, and psychedelics in medicine. She is a Distinguished Fellow with the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and consults with entertainment industry professionals from Netflix to Warner Brothers to improve mental health representation in media.

Join us as we explore Dr. Hartselle's expertise in psychedelic therapy, the connection between mental health and creativity, and her perspectives on the future of mental healthcare.

Tell us about your background and how you became interested in psychiatry, particularly your work with psychedelics in mental healthcare.

I actually entered medical school positive that I wanted to do anything but psychiatry. At the time, Frasier was popular, and I thought, "Why would you go to medical school for that long, learn procedures and how to deliver babies, just to sit and talk to someone?" But as medical school progressed, my friends noticed that all I talked about was psychiatry. What I learned is that you can develop any psychiatric career you want — we do neuro exams, we draw blood, I get to be very medical in my practice if I choose.

I've been in practice for 11 years now, and what I love about psychiatry is this incredible privilege of getting to know people deeply. I have my friends, family, and colleagues, but then I have this group of people I talk to every week for an hour. I've ushered people through marriages, divorces, births, deaths — it's an indescribable privilege.

The psychedelics work started about five years ago when I was giving lectures to Brown medical students. I mentioned future possible treatments like psilocybin and MDMA in passing, and a week later, students approached me asking if I'd teach a course on psychedelics. They said there was no one else. My entire knowledge base was on that one slide! But the students helped set everything up, and we brought in principal investigators from major studies across the country. We've now been teaching this course for four years.

Can you explain the current state of psychedelic therapy and how it differs from traditional psychiatric treatments?

The current state is fascinating but complex. These substances were previously classified as Schedule I, meaning they were designated as having zero medical benefit and high addiction risk. Nixon's administration shut down research, and it resumed later in Switzerland.

What we've discovered is remarkable: several classical psychedelics are actually impossible to become addicted to. If you take them multiple times in a short period, by the third time, there's no response — you've saturated the system. Many are also impossible to overdose on, though there are important safety considerations for people with histories of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

Currently, only ketamine is legal for therapeutic use, though it's technically a dissociative rather than a classic psychedelic. MDMA was close to FDA approval but was recently rejected — the FDA cited difficulty controlling for variables like the extensive psychotherapy component. Psilocybin will likely be approved in 2026.

What makes these treatments revolutionary is their sustained efficacy. We're seeing results that last months or years from just one or two doses, compared to our current medications that must be taken daily and often just manage symptoms rather than cure conditions.

What conditions are showing the most promise in psychedelic treatment?

Treatment-resistant depression is showing incredible promise, along with severe major depressive disorder, alcohol use disorder, and nicotine addiction — which is notoriously difficult to treat because nicotine is actually more addictive than opiates.

End-of-life anxiety is where much of the research started, at NYU where I did my residency. They worked with hospice patients, mostly those dying of cancer, and found significant improvements in end-of-life anxiety and self-proclaimed peace with death that was sustained until the end of life.

MDMA has shown remarkable results for PTSD — people would enter studies with severe PTSD and leave without the diagnosis entirely, with results sustained months and years later. Right now, we don't have a medication for PTSD; we use multiple medications to lower symptoms and work with therapy over years. MDMA shows potential for what appears to be a cure rather than just management.

We're also seeing promising research on eating disorders, anxiety, OCD, and substance use disorders.

You'll be discussing the connection between mental health and creativity at your talk at Newport Art Museum. How do you see this relationship, particularly when it comes to artists navigating emotional wellbeing?

This connection is so significant that we actually have different psychological testing scales for artists versus non-artists. Artists come up with creative ways to answer questions that might look concerning in someone else but make perfect sense for an artist because they see the world differently.

Historically, we see successful artists struggling deeply with mental illness. Being depressed, anxious, or even psychotic can narrow your world, while being an artist involves seeing the world much wider than most of us do. When artists emerge from depression, that's often when creativity flows most powerfully. Mania can create an even wider perspective and tremendous creativity, though it comes with behavioral risks.

Given Bobby Anspach's work was centered on creating transcendental experiences and deep human connection, how do you think psychedelic therapy might relate to or enhance the kind of profound experiences his art aimed to create?

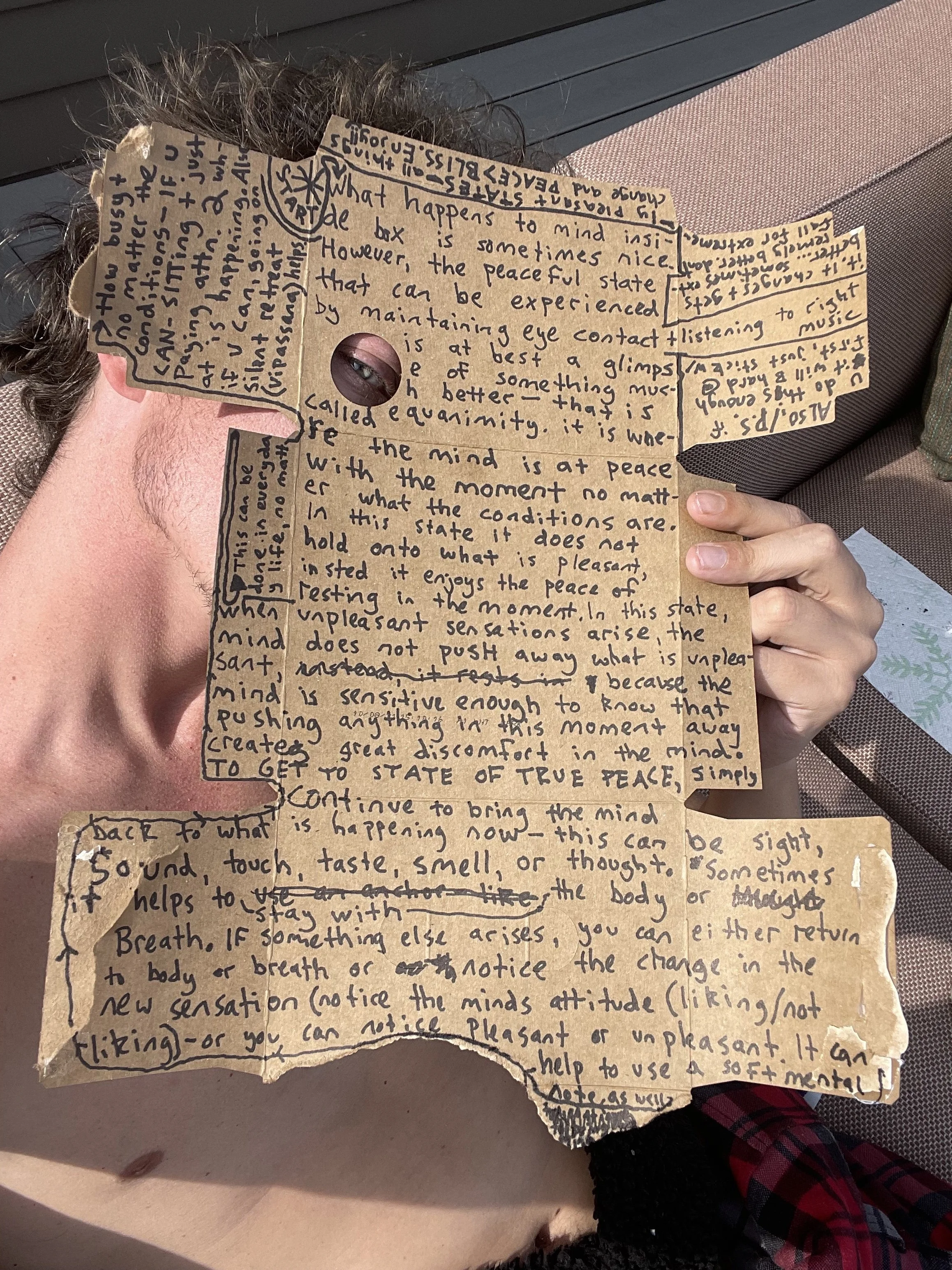

The connection is profound. Our brains are very efficient — from a young age, we develop neural pathways that become automatic, including negative thought patterns and trauma responses that may no longer serve us. These loops become very efficient but hard to break.

Psychedelics light up almost all areas of the brain simultaneously, creating new connections where they usually don't exist. This opens what we call a "critical learning window"— allowing those limiting loops to flatten and expand our perspective, much like art does.

When I experienced Bobby's installations at the Newport Art Museum, I thought, "This is a profoundly joyful psychedelic experience." I would love to study people's brains with functional MRI while they're experiencing his work. His installations create transcendental experiences without substances — one focuses on connection with yourself, the other on connection with others. You emerge with a sense of wonder and deep connection, even with strangers.

Bobby intuitively understood how the brain needs to work to heal, something scientists are just beginning to comprehend. That's what genius artists do — they contribute enormously to how we live and heal.

What ethical considerations surround psychedelic therapy, especially as it becomes more mainstream?

First, we must acknowledge the indigenous roots of these medicines. Psilocybin was "discovered" by well-intentioned researchers who went to Oaxaca and learned from a shaman, but their subsequent article in Time led to tourism that decimated the town and resulted in the shaman being ousted. We now know psilocybin grows naturally in multiple U.S. states, making that disruption unnecessary.

Safety is paramount. People need to thoroughly vet providers — what experience do they have? What safety protocols? Because you're in a vulnerable state, we recommend two therapists present during sessions for safety and boundary protection. Unfortunately, every profession has ill-intentioned people, and there have been reports of boundary violations.

There's also the reality of unregulated access. While I professionally have to recommend against recreational use due to risks like fentanyl contamination, I understand people seek these experiences when traditional treatments aren't working. These are powerful medicines that should be respected and carefully administered.

What key takeaways do you hope guests of your talk will leave with?

I want people to understand that many of these substances are remarkably safe for most populations — they're not addictive, you can't overdose on several classes of them. There's often fear around psychedelics, understandably, but the research is promising.

In psychiatry, our current medications are frustrating — they're long-term, difficult, and we don't have treatments for many conditions. While talk therapy is impactful, it takes years, and sometimes we don't have years to wait to feel better. The possibility of a two-dose intervention with sustained results is incredibly promising.

However, we can't consider this a panacea. We must be critical about how we implement these treatments and who provides them.

I also want people to know that interacting with art is something I actually prescribe to my patients. There are ways to have psychedelic-like experiences through art, breathwork, and other methods that don't involve substances. Bobby's installations are a brilliant example of this.

Finally, if you're struggling, there are resources available — suicide hotlines, research sites if you're in a state where these treatments aren't available. I have hope for the future of mental healthcare, and I believe art should be part of that healing process.

That said, psychedelics can be dangerous for those with personal or family histories of psychotic illnesses. They can unmask a previously undiagnosed disorder or worsen an existing one. This is another critical reason why working within a research program or with a trained professional — someone who can provide safe, legal access — is so important for those seeking care.

Resources for Mental Health Support

Immediate Crisis Support:

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988 (24/7 crisis support)

Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI): 1-800-950-NAMI (6264) for support and resources

Finding Mental Healthcare:

Psychology Today: psychologytoday.com - Find therapists, psychiatrists, and support groups in your area

SAMHSA National Helpline: 1-800-662-4357 - Treatment referral and information service

Open Path Psychotherapy Collective: openpathcollective.org - Affordable therapy options

Psychedelic Research Participation:

ClinicalTrials.gov: Search "psilocybin," "MDMA," or "psychedelic" to find ongoing studies

Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic Research: hopkinspsychedelic.org

NYU Langone Center for Psychedelic Medicine: nyulangone.org/locations/center-psychedelic-medicine

UCSF Neuroscape Psychedelics Division: neuroscape.ucsf.edu

Legal Psychedelic Therapy:

Ketamine clinics: Search "ketamine therapy" + your location

Oregon Psilocybin Services: oregon.gov/oha/PH/PREVENTIONWELLNESS/Pages/Psilocybin-Services.aspx

Colorado Natural Medicine: colorado.gov/natural-medicine (implementation ongoing)

Art and Mental Health Resources:

Art therapy programs: Search local hospitals, community centers, and mental health clinics

Museum wellness programs: Many museums offer therapeutic programming

Creative arts therapies: Search for certified art, music, or movement therapists

Important Note: Always consult with healthcare professionals before considering any new treatment. If you're interested in psychedelic therapy, work only with licensed providers in legal settings, and never attempt to self-medicate with unregulated substances.